“In other news, standardized test results came in this afternoon. We ranked forty-third out of the forty-nine high schools in the city.

...

We’ll try for number one next year.”

—from Exception to the Rule, Dave Harris

Standardized testing has a long and divisive history in American education. Today, it holds immense power over the lives and futures of students. When the United States first adopted formal written testing in the mid-1800s, the practice had two aims: to sort students into levels of proficiency and to monitor the efficacy of American schooling. Testing proponents believed that it was a tool of equity, and that implementing standardized assessments would ensure that children across the country—regardless of race, class, or economic position—would receive the same standard of education.

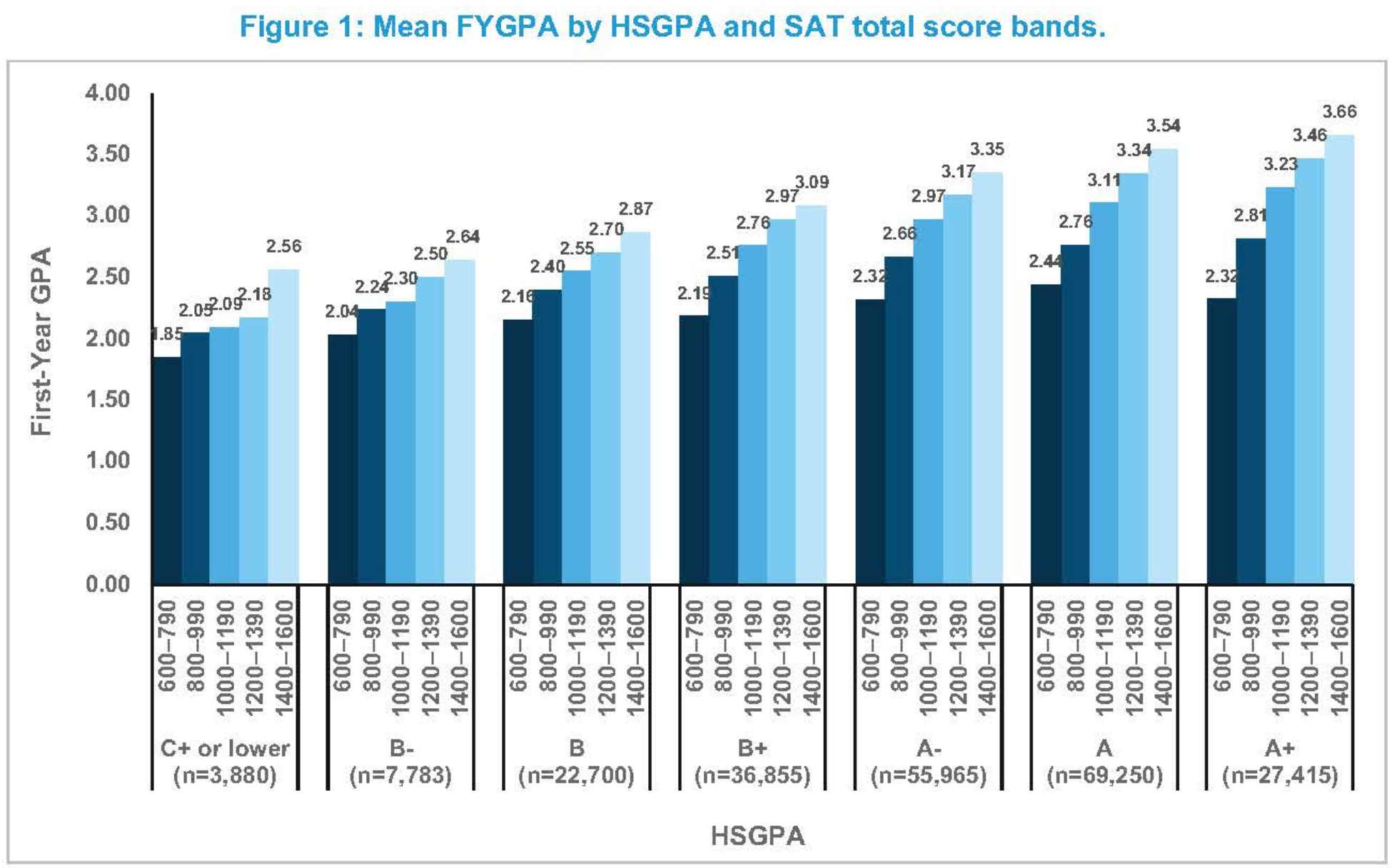

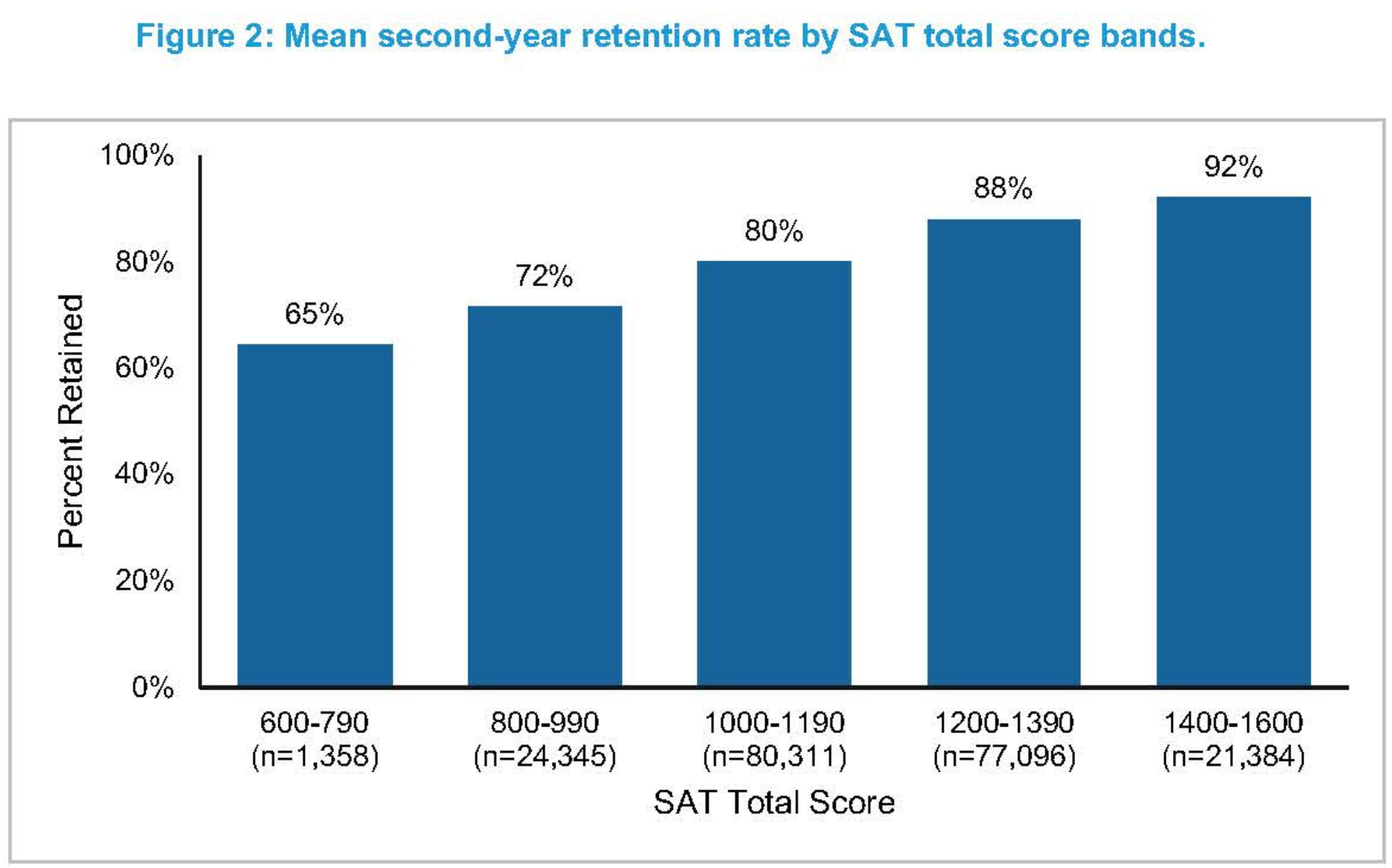

Today, the SAT, or Scholastic Assessment Test, is one of the most taken standardized test in the United States. More than 1.9 million students in the class of 2023 took the test at least once, and performance is a major factor in admissions at colleges and universities across the country. Proponents of the test cite its accuracy in anticipating students’ success in college. In a 2016 validity study, the College Board determined that SAT is “strongly predictive of college success” as defined by first-year GPA and second-year retention rate.

(Both from College Board validity study)

Many SAT proponents believe that the test is a more equitable college admissions tool than other factors colleges consider. An applicant’s GPA and transcript are directly affected by their school’s AP or Honors course offerings—not to mention the potential benefit of expensive tutoring or parents who have completed similar coursework. An applicant’s resume is dependent upon having time, access, and money to engage in extracurricular activities.

Compared to these factors, many consider the SAT a fair playing field. “Our research shows standardized tests help us better assess the academic preparedness of all applicants, and also help us identify socioeconomically disadvantaged students who lack access to advanced coursework or other enrichment opportunities that would otherwise demonstrate their readiness for MIT,” wrote Stu Schmill, dean of admissions and student financial services at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explaining their 2022 decision to reinstate standardized testing after pausing the requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. “We believe a requirement is more equitable and transparent than a test-optional policy.”

However, the early history of the SAT is not one of equity. Its first iteration was developed in 1926 as an aptitude test for the U.S. Army. A primary psychologist in the design of this original test was Carl Brigham—a prominent eugenicist of the 1920s. Brigham’s 1923 book, A Study of American Intelligence, holds up standardized testing as a means of demonstrating “the intellectual superiority of our Nordic group over the Alpine, Mediterranean, and negro groups.”

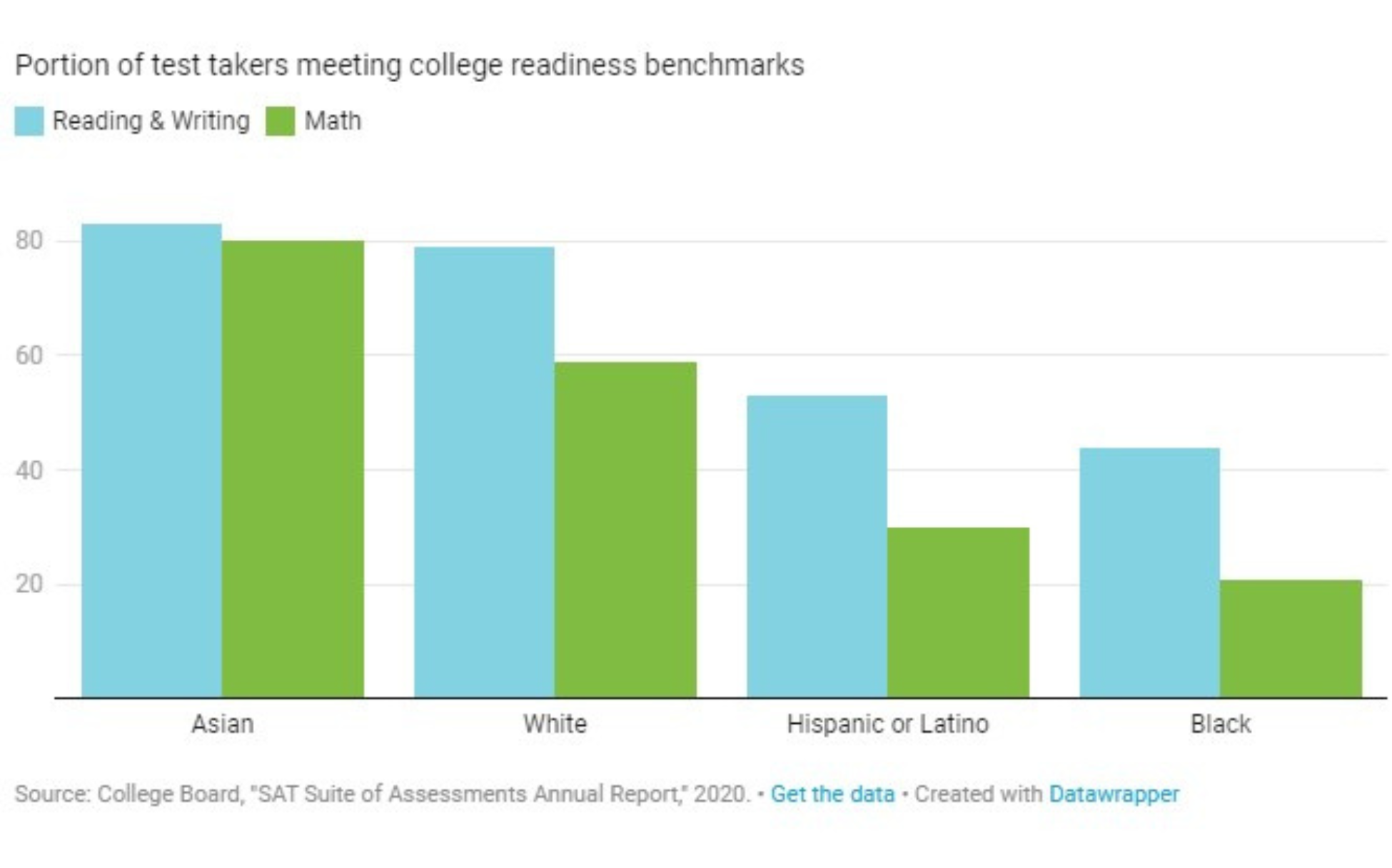

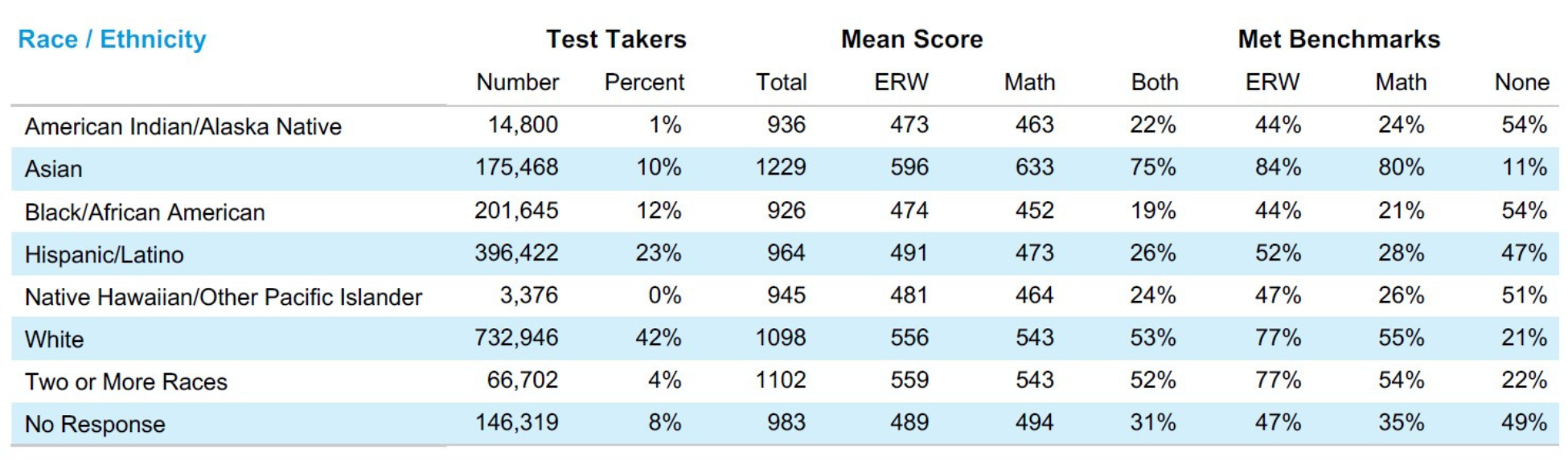

While much about the test has changed in the last century, modern critics of the SAT note the strong racial and economic bias in test performance. Researchers see a persistent “race gap” in scores—particularly for Black students. In 2022, the mean score for Black test-takers was 172 points lower than the mean score for white test-takers. 5% of white students scored between 400-790, the lowest score category, while 25% of Black students scored in that range. And where 7% of white test-takers scored between 1400-1600, the highest scoring range, only 1% of Black test-takers received scores in that margin. While the College Board’s validity study did not include race as a variable, further studies have determined that the SAT is far less accurate in predicting college success for Black and Hispanic or Latino applicants.

(Above from Brookings article)

(Above from 2022 College Board Data)

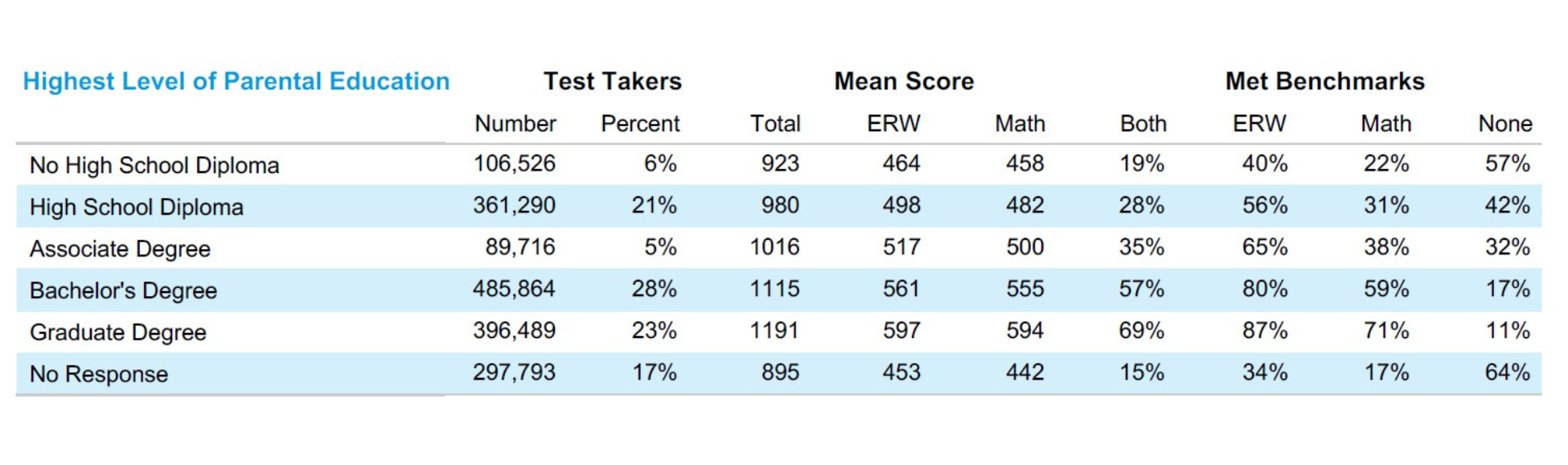

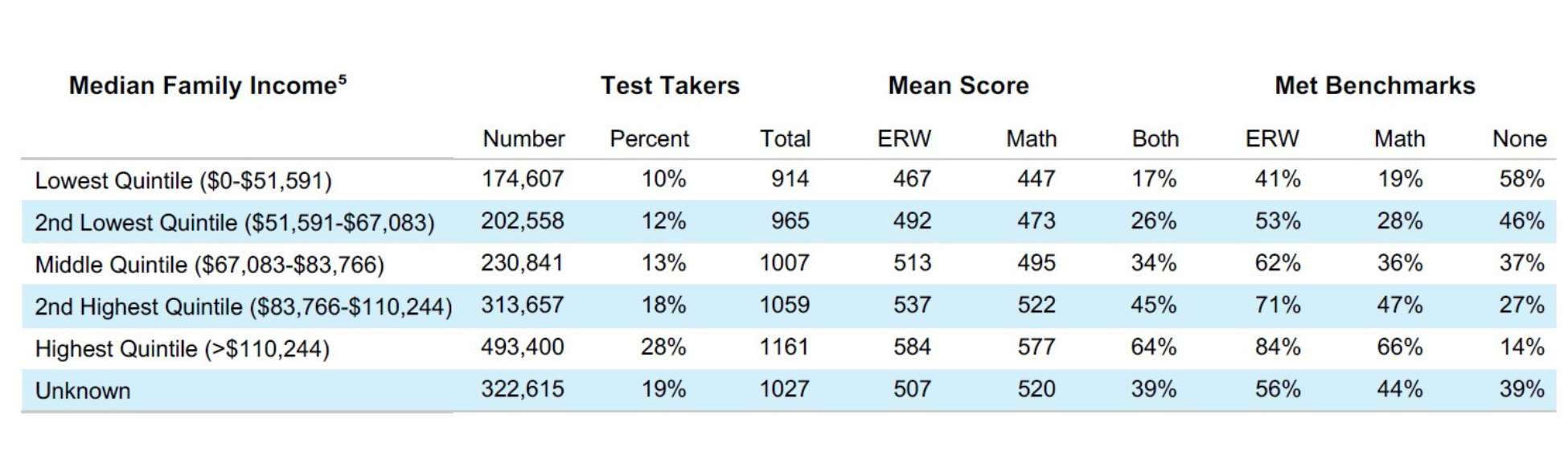

The test shows similar disparities on other socioeconomic axes. On average, test-takers whose parents hold high school diplomas scored 57 points higher than those whose parents do not. The same trend continues—the more advanced a parent’s highest degree earned, the higher their child is likely to score. A student’s financial situation is also likely to be reflected in their test performance, with education researchers Ember Smith and Richard V. Reeves noting that family income is a “shockingly good predictor of standardized test performance.” Students whose families earn between $0-$51,591 per year saw a mean score of 914, while students whose families earn more than $110,244 annually saw a mean score of 1161.

(Both from 2022 College Board Data)

Proponents of the SAT attribute these disparities to pre-existing problems in the American education system that appear along racial, class, and economic lines—that redlining and inequitable funding practices set students up for failure long before they register for the test. Its opponents argue that problems lie in the test itself. “We still think there’s something wrong with the kids rather than recognizing there’s something wrong with the tests,” writes Ibram X. Kendi, the founder of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University. “Standardized tests have become the most effective racist weapon ever devised to objectively degrade Black and Brown minds and legally exclude their bodies from prestigious schools.”

—Nora Geffen