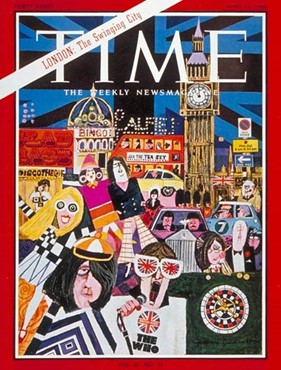

From “The Swinging City,” Time Magazine, April 15, 1966:

In this century, every decade has had its city. The fin de siècle belonged to the dreamlike round of Vienna, capital of the inbred Habsburgs and the waltz. In the changing '20s, Paris provided a moveable feast for Hemingway, Picasso, Fitzgerald and Joyce, while in the chaos after the Great Crash, Berlin briefly erupted with the savage iconoclasm of Brecht and the Bauhaus. During the shell-shocked 1940s, thrusting New York led the way, and in the uneasy 1950s it was the easy Rome of la dolce vita. Today, it is London, a city steeped in tradition, seized by change, liberated by affluence, graced by daffodils and anemones, so green with parks and squares that, as the saying goes, you can walk across it on the grass. In a decade dominated by youth, London has burst into bloom. It swings; it is the scene.

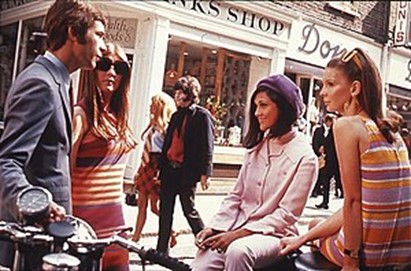

This spring, as never before in modern times, London is switched on. Ancient elegance and new opulence are all tangled up in a dazzling blur of op and pop. The city is alive with birds (girls) and beatles, buzzing with minicars and telly stars, pulsing with half a dozen separate veins of excitement. The guards now change at Buckingham Palace to a Lennon and McCartney tune, and Prince Charles is firmly in the longhair set. In Harold Wilson, Downing Street sports a Yorkshire accent, a working-class attitude and a tolerance toward the young that includes Pop Singer "Screaming" Lord Sutch, who ran against him on the Teen-Age Party ticket in the last election. Mary Quant, who designs those clothes, Vidal Sassoon, the man with the magic comb, and the Rolling Stones, whose music is most in right now, reign as a new breed of royalty. Disks by the thousands spin in a widening orbit of discotheques, and elegant saloons have become gambling parlors. In a once sedate world of faded splendor, everything new, uninhibited and kinky is blooming at the top of London life.

Excerpts from Dylan Jones’s 2020 GQ article, which looks back at London in the 1960s, and the famous Time Magazine article on “London: The Swinging City”:

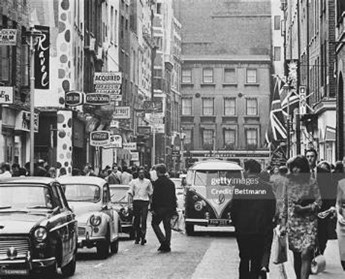

Looking back now, it almost seems as though everything happened at once. In a decade dominated by youth, London had burst into bloom. It was swinging, and it was the scene. The Union Jack suddenly became as ubiquitous as the black cab or the red Routemaster, and all became icons of the city. Carnaby Street’s turnover was more than £5 million in 1966 alone. Quite simply, London was where it was at. Fuelled by growing prosperity, social mobility, post-war optimism and wave after wave of youthful enterprise, the city captured the imagination of the world’s media. Here was the centre of the sexual revolution – the pill had been introduced in 1961 – the musical revolution, the sartorial revolution. London was a veritable cauldron of benign revolt.

Carnaby Street wouldn’t be pedestrianised until 1973 (to cope with the human traffic resulting from pieces like the one in Time), and was still being besieged by retailers trying to exploit the area’s success. Tommy Roberts opened Kleptomania in Kingly Street, just behind Carnaby Street, in the summer of 1966, and it quickly became one of the “in” places. It was curatorial in essence and, as well as clothes, Roberts filled the shop with Edwardian wind-up gramophones, sepia-toned erotica, opium pipes, a coffee table made out of an elephant’s foot – “weird bits of junk”, according to Roberts.

A new London was mushrooming into life. Winston Churchill was dead, abortion was about to be made legal, and happiness seemed exponential. Britain was experiencing almost full employment, and so it never occurred to anyone that there might not be a job waiting for them when they left school or their red-brick university. And the job you wanted was probably in London. It was all about the city. Turn around, you saw an actress. Look across the road, you saw a potential model spill out of a taxi. Over there, by the Chelsea Potter, wasn’t he a writer? And wasn’t he standing next to the guy who managed that group? Or was it the other guy, the gay one who was trying to organise a be-in at the Roundhouse?

Everywhere you looked you saw an aspiring this, a potential that. And they were all dressed up to the nines. Every window had a Union Jack decal, every poster was emblazoned with a yellow flower or a caricature of a Regency dandy, only this time wearing coral-coloured loon pants and a paisley cravat. If you walked along the Kings Road, as part of the Saturday afternoon procession, you would be assaulted by a barrage of noise escaping from every shop doorway: “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” by the Walker Brothers, “Paint It Black” by the Rolling Stones and “Paperback Writer” by the Beatles. You might hear the odd bootleg, too, smuggled over from New York or Los Angeles. There were huge music scenes on both coasts, yet bands had to be accepted - in London before they could properly get - traction at home.

This would be the year in which Harold Wilson’s freshly elected government would sanction the BBC’s decision to launch an all-day pop radio station coincidentally at precisely the same time that their pirate rivals – such as Radio Caroline – were being hounded out of existence by new legislation. This was also the year in which Bill Cotton, then the assistant head of light entertainment at BBC One, decided the channel needed a British version of The Tonight Show, which was hosted by Johnny Carson on the American network NBC.

A year earlier, Diana Vreeland, the editor of American Vogue, had said, “London is the most swinging city in the world,” putting into words what a lot of people on both sides of the Atlantic had been thinking for a while. “The caste system, in short, is breaking down at both ends,” ran an editorial in the Daily Telegraph. “The working class are busting out of the lower depths and invading fields where they can make more money and the upper class is breaking down walls to get into the lower levels where they can have more fun.”

“It’s often explained as a result of the post-World War II kids all coming of age at just the right time,” said Paul McCartney, the ultimate Sixties London immigrant. “And, as well, we all ended up in the same city. We’d come down from Liverpool – various people had come over from America to London: the global village was just beginning and opening its doors. We went to the same parties, same galleries. It was a scene... The swinging London scene.” There were more divergencies than commonalities among the thousands of people who converged on London in the mid-Sixties, yet collectively, together, they were responsible for one of the most creative periods of post-war Britain, a cultural groundswell that would be destined to repeat itself mid-decade, every decade, for the next 50 years. The first iteration was Swinging London, followed by punk in the Seventies, the new romantics of the Eighties, and Britpop in the Nineties.

…The early Sixties were full of people from East London, South London and the “wrong” parts of West London who were infiltrating parts of the city that had previously been out of bounds. People who were not only moving in worlds their parents would never have dared to enter, but also inventing new ways to make a living, creating a lifestyle industry that had never been seen before. London’s seemingly unwitting metamorphosis from a gloomy, grimy post-war capital into a bright, shining epicentre of style was due largely to two factors: youth and money.

The Fifties baby boom meant the urban population was the youngest it had been since Roman times, with 40 per cent of the population under 25 by the mid-Sixties. The abolition of national service for men in 1960 allowed young people to have more freedom and fewer responsibilities than any generation before them.

…For many, sex was on the agenda like never before, especially if you were in the image business. Opportunity was the prime catalyst – opportunity and proximity. Men and women were mixing like never before, in social circumstances that hadn’t existed 12 months previously. If you wanted it, sex was everywhere.

“It was like a tap had been turned on,” said one photographer. “Girls were walking around with inquisitive looks on their faces, almost daring you to approach them. There was just so much sex... If you were cheeky, or at least if you were prepared to ask, you had a great time. All my friends from the East End couldn’t believe all the pussy I was getting. They thought I dressed like a poof, but they started to see why when they saw how much I was getting. Nobody was exclusive in those days, no man anyway, and not many women. This was the Sixties, and girls had just discovered that they liked having sex and men weren’t about to complain. So there were always lots of other girls around. It never entered my mind not to be unfaithful, because that’s just how life was.”