Note: A longer version of the essay appears in the Studio Theatre Performance Guide

“She’s a Chicago writer but she was published by Broadside Press, an African-American publisher in Detroit, before she was published by HarperCollins. I have a Broadside anthology that I won in first grade, as a prize in an MLK essay contest. Miss Gwendolyn Brooks was one of the poets in that anthology. I’ve told the Pipeline cast about the particular incident that made me choose the poem. When I was in eighth grade the boys had to perform “We Real Cool” at our Black History Pageant. I had to perform Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise,” and I wanted to perform it as well as the boys did theirs. The way those boys performed that poem has stayed with me for the rest of my life. They were so good. At age 13 or 14 they understood the flip that happens in the poem. And that used to haunt me. I’ve taught that poem to teenagers. There’s some kind of ancestral power in it when I see it written. I used to write it on the board when I walked into a classroom and just let it live there. It’s magic to me.” —Dominique Morisseau

Protest and revolution were evident in Gwendolyn Brooks' poetry long before she was an active participant in the Black Arts Movement. Her work centers around the people she observed growing up and living in Chicago—lower class Black Americans whose primary focus was maintaining a comfortable life and family. In scenes of unembellished struggle, ordinary celebrations, and simple everyday experiences, Brooks asserts the primacy of Black culture. Her work moves in many forms, including traditional ballads, rhythm and blues, free verse, and pointed experimentation with lyricism in narrative and dramatic, poetic structures. Though the stories in the experimental pieces tend to be simply about surviving from day to day, her characters are remembered for their sense of self-importance and insistence on cultivating self-preservation and expansion beyond systems of oppression.

The energy of self-determination and adolescent rebellion are captured in “We Real Cool”. The poem is about a group of boys that Brooks observed at a pool hall during school hours. Rather than questioning why they were skipping school, she asked, "I wonder how they feel about themselves. And, just perhaps they might have considered themselves contemptuous of the establishment…"

WE REAL COOL. WE

LEFT SCHOOL. WE

LURK LATE. WE

STRIKE STRAIGHT. WE

SING SIN. WE

THIN GIN. WE

JAZZ JUNE. WE

DIE SOON

This question of a Black person's relationship to, or investment in, 'the establishment' is at the core of Nya and Omari's experiences in Dominique Morisseau's Pipeline. The poem moves metaphorically through the play as mother and son reckon with systemic and institutional racism in high school academia.

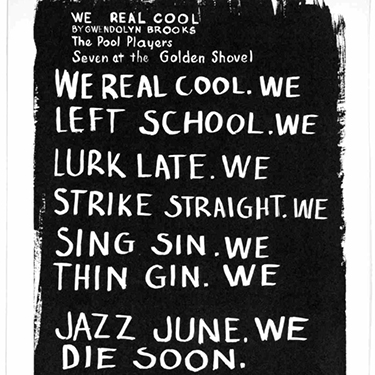

“We Real Cool” first appears in Pipeline as the subject of Nya's literature lesson. She asks her students to examine two editions of the poem: one released by Broadside Press, an independent Black publisher and one by Harper Collins, a commercial white-owned press. The Broadside Press version breaks traditional rules about form and publication—the design inverts standard printing conventions as the typeface is white and the background is black, all letters are capitalized, and the vernacular of the characters is lifted by the use of nonstandard grammatical structures. Each of these transgressions asserts the piece's revolution and Blackness.

Meanwhile, in the Harper Collins edition of “We Real Cool”, some of these markers of Black aestheticism are erased—only the words at the top of each stanza are capitalized, and the text is printed on white paper with black ink. While Nya and her students unpack the meaning of the poem and its divergent editions, her son Omari appears onstage to respond to each line. Like the Seven Boys, Omari is contemptuous of his academic institution and searching for where he belongs. The system wasn’t made for, and continues to fail, them. Omari, at this moment, becomes the physical manifestation of Brooks’ characters and their conflict. Their decision to transgress, while revolutionary, can come with significant consequences.

—Manna-Symone Middlebrooks